SOC 2 is dead, long live SOC 2!

With a healthy dose of in-depth continuous assurance

Originally posted on the GRC Engineering Community Blog hereIn-depth continuous assurance over shallow periodic monitoring

This is core value #5 in the GRC Engineering Manifesto. I've been thinking about it a lot lately, especially given all of the dunking on SOC 2 that has happened over the last year, such as all the problems with "compliance commoditization" and "SOC-in-a-box" and who is to blame for it all (Compliance Automation vendors? the AICPA? audit firms? third-party risk management teams? all of the above?!)

There’s a growing chorus of folks in our industry who claim that SOC 2, and the AICPA’s stewardship of it, is thoroughly busted. On the other hand, auditors and CPAs claim that low quality or incompetent auditors are the problem and SOC 2 itself is fundamentally sound.

In my mind, there are valid points on either side of this debate.

But I also think there are deeper issues with SOC 2 (and other security compliance frameworks) that haven't been discussed as much, let alone what it looks like for those issues to be resolved.

In this post, I’m going to lay out what I believe these deeper issues are, paired with a vision for what a better approach could look like for security compliance frameworks to finally provide in-depth continuous assurance about an organization’s security controls.

The problem with SOC 2? It SOCs 2 much!

My first premise on this topic is this: there has never been a time when SOC 2 - or really any industry standard “security compliance audit” - was ever good enough, in any way, shape, or form at providing sufficient assurance about an organization’s security controls.

The fundamental issues with SOC 2’s assurance value predate “SOC-in-a-box” automation products. These issues have been present throughout SOC 2’s history: from SAS 70 being used before the cloud was The CloudTM (RIP ASPs); to SSAE 16 establishing SOC as the successor to SAS 70; to SSAE 18 replacing SSAE 16; and all the way up to the 2022 “Revised Points of Focus” update to the 2017 Trust Services Criteria. SOC-in-a box compliance commoditization has merely made it easier to see the deep flaws with security compliance frameworks and audits of all kinds.

The deeper issues with security compliance frameworks and audits

Every security compliance framework shares the same fundamental ingredients:

A set of requirements or objectives that controls must achieve

An audit methodology for determining how well controls meet said requirements

A reporting artifact to convey assurance signals to stakeholders via findings and opinions from the audit

How these ingredients are implemented vary from framework to framework. But aside from maybe one framework, they all do a poor job at putting these ingredients together in ways that provide in-depth continuous assurance.

Let's unpack the common flaws with each of these one by one.

Control requirements: vague solutions for unclear problems

The biggest issue with how control requirements are implemented is that they are defined without any explicit association or relevance to the threats they are intended to guard against (with the exception of HITRUST - but even it suffers from deeper issues with the other two ingredients I described above).

In the case of SOC 2, control requirements in the form of Trust Services Criteria (TSC) and Additional Points of Focus (PoFs) are so vague that they are virtually useless for ensuring organizations consistently design controls that are proven to be effective at protecting against relevant threats.

Let’s use SOC 2’s Common Criteria (CC) 6.6 as an example:

CC 6.6 TSC: “The entity implements logical access security measures to protect against threats from sources outside its system boundaries”

CC 6.6 PoF: “Identification and authentication credentials are protected during transmission outside its system boundaries”

Imagine for a moment if this same kind of requirements framework were used for, let’s say, car safety. In such a bizarro world of vague, loose, and totally optional car safety requirements (which basically existed for ~100 years), it would be like having a TSC stating “the car implements physical restraint measures to protect passengers against threats from abrupt deceleration events” and a PoF stating “passengers are protected during high speed movements on roadways.”

This clearly would be a virtually useless way to not only provide sufficient assurance about the safety of any given car, but to ensure that all cars are equipped with universally-applicable safety measures that protect against common threats that all passengers face.

This has certainly been the case for SOC 2 and other security compliance frameworks. They need to evolve their underlying controls requirements model to be focused on specific requirements that are known to be effective at protecting against common threats.

Audit methodologies: 20th century approaches applied to 21st century systems

This is the area that SOC 2 and other security compliance audits get criticized about the most: point-in-time screenshots, hours upon hours of walkthrough meetings, and quarterly lookback reviews all make the audit world go ‘round.

While these tend to be the most frustrating and inefficient aspects of audits for those who undergo them, I find that these are not the most problematic aspects of how current audit methodologies severely limit the assurance value such audits can provide. The biggest shortcoming with our security compliance audit methodologies is that we almost never assess historical evidence for technical controls’ operating effectiveness. This can result in huge misses about the reality of an organization’s’ control operating effectiveness which is best summed up with this meme:

Not only that, but auditors still primarily use evidence sampling methods (both statistical and nonstatistical) to draw conclusions about control operating effectiveness. However, there have been long-running concerns within the accounting profession with how auditors exercise too much professional judgment, rather than more strictly sticking to rigorous statistical principles, when determining what kinds of sampling methods to use and how to apply them. This can create excessive risks with drawing inaccurate conclusions about control operating effectiveness.

Now you might be thinking, “wait, my auditors always ask for samples of control evidence that include past dates during my audit period!” - and to that I would say: yes, you’re correct!

But this usually is only done for process controls that are inherently transactional in nature. For example: access requests, access (de)provisioning events, change requests, etc. which are operated via ticketing systems which necessarily means there is always historical evidence of a control’s operations.

However, technical controls that are inherently stateful in nature, such as at-rest data encryption, endpoint detection & response (EDR) tooling, or web application firewalls (WAFs), are only assessed by auditors for their current state. It doesn’t matter how long your audit period is - it could be 1 month, 6 months, or 12 months - your technical controls’ operating effectiveness is not being properly tested.

Why might this be? Well, a lot of organizations likely aren’t maintaining a historical audit trail of their technical controls’ state over time, and for whatever reason most auditors don’t think to push their clients to provide such historical evidence, even as an opportunity for improvement to implement before the next audit happens.

We need to change our audit methodologies to fully cover historical control operating effectiveness during the entirety of an audit period and to analyze the full population of a control, especially for technical controls. Otherwise, we’re only providing (very weak) assurance about controls’ operating effectiveness for the brief moment in time we gather evidence about their state.

Reporting artifacts: static documents for providing assurance about dynamic environments

Take a look at the results from this very unscientific poll I conducted on LinkedIn to gauge what our profession thinks the “use by” date for your SOC 2 Type II report should be before its assurance value expires. The results are fascinating:

It’s shocking that anyone thinks that a SOC 2 Type II report provides sufficient assurance up to 12 months after it is issued. Modern software-as-a-service organizations are making dozens, hundreds, and even thousands of changes to their systems every day. Every change poses varying risk to the operating effectiveness of the controls that exist in and around said systems: entire workloads deployed without threat detection controls in place (ouch!), new data stores deployed without at-rest encryption enabled (oops!), or a new web API released on a domain that your WAF isn’t configured to protect (oof!).

Now let’s take into account the fact that it can take weeks to go from the last piece of evidence being reviewed by your external auditor and your SOC 2 Type II report being finalized. Why do we treat this status quo of security compliance reporting artifacts as having any assurance value more than 1 week after they’ve been finalized?

We need a new kind of reporting artifact that is dynamic enough to reflect the current, and historical, operating effectiveness of an organization's controls. Static PDFs aren’t gonna cut it anymore.

A vision for security compliance audits that provide true in-depth continuous assurance

The problems with our current security compliance audit frameworks are clear: control requirements are very vague and not explicitly threat informed, audit methodologies are way too narrowly focused, and static reporting artifacts quickly become outdated views of highly dynamic control environments.

To overcome these fundamental flaws with SOC 2 and other security compliance frameworks, I’d like to propose a new framework for providing in-depth continuous assurance about an organization’s controls viability and operating effectiveness.

This framework:

Should have specific control requirements that are explicitly related to relevant threats

Should facilitate and require comprehensive control auditing methodologies that match the scale and depth of modern organizations’ control environments

Should provide a reporting artifact that is as dynamic as the control environments for which it is intended to describe the operating effectiveness

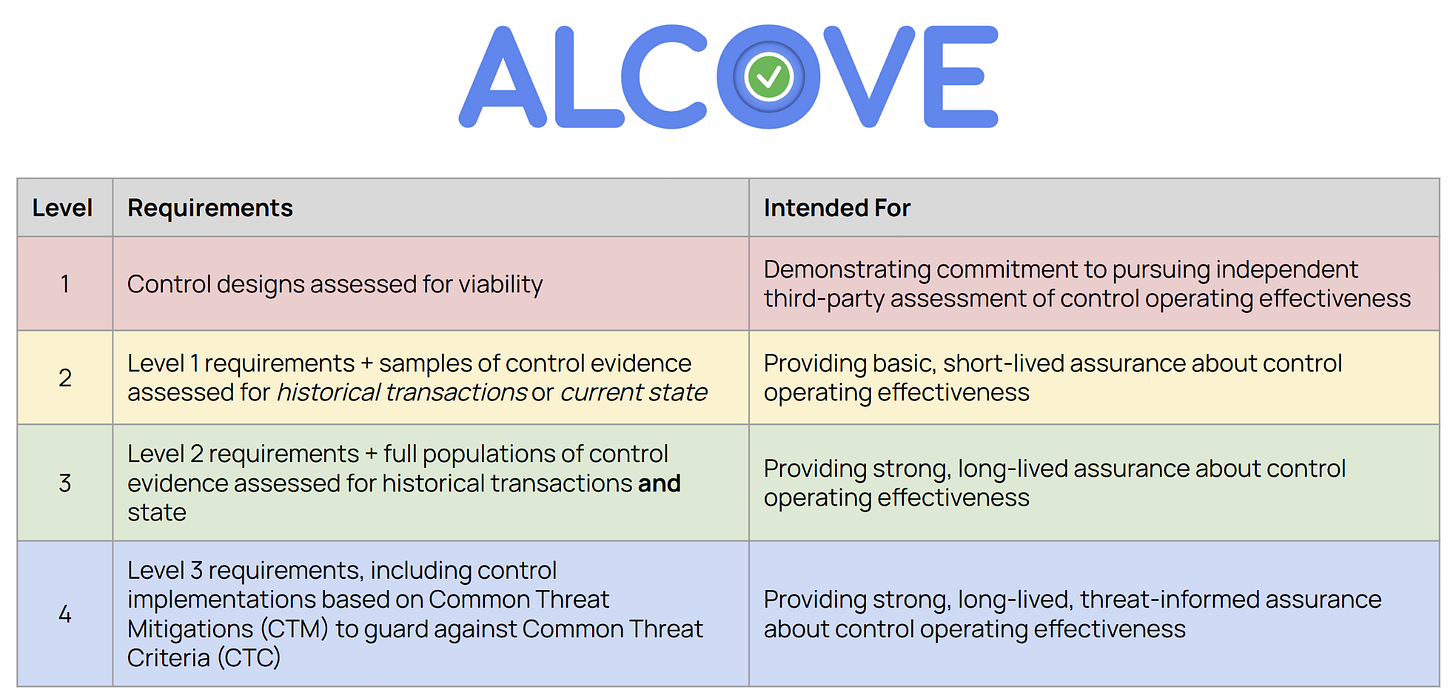

I call this framework ALCOVE: Assurance Levels for Control Operating Viability & Effectiveness.

Rather than totally reinventing the wheel, I believe we should draw inspiration from wheels that have already been invented from similar disciplines within security and software engineering. There already exists a scalable and robust security assurance framework that is being adopted by software providers, large and small, across various industries: Supply-chain Levels for Software Artifacts, or SLSA ("salsa") for short, which is a software supply chain security assurance framework.

Similar to SLSA, ALCOVE has various levels of assurance that an organization can strive to provide, allowing for flexibility for organizations and their stakeholders alike to provide and require establishing certain levels of assurance based on their specific needs.

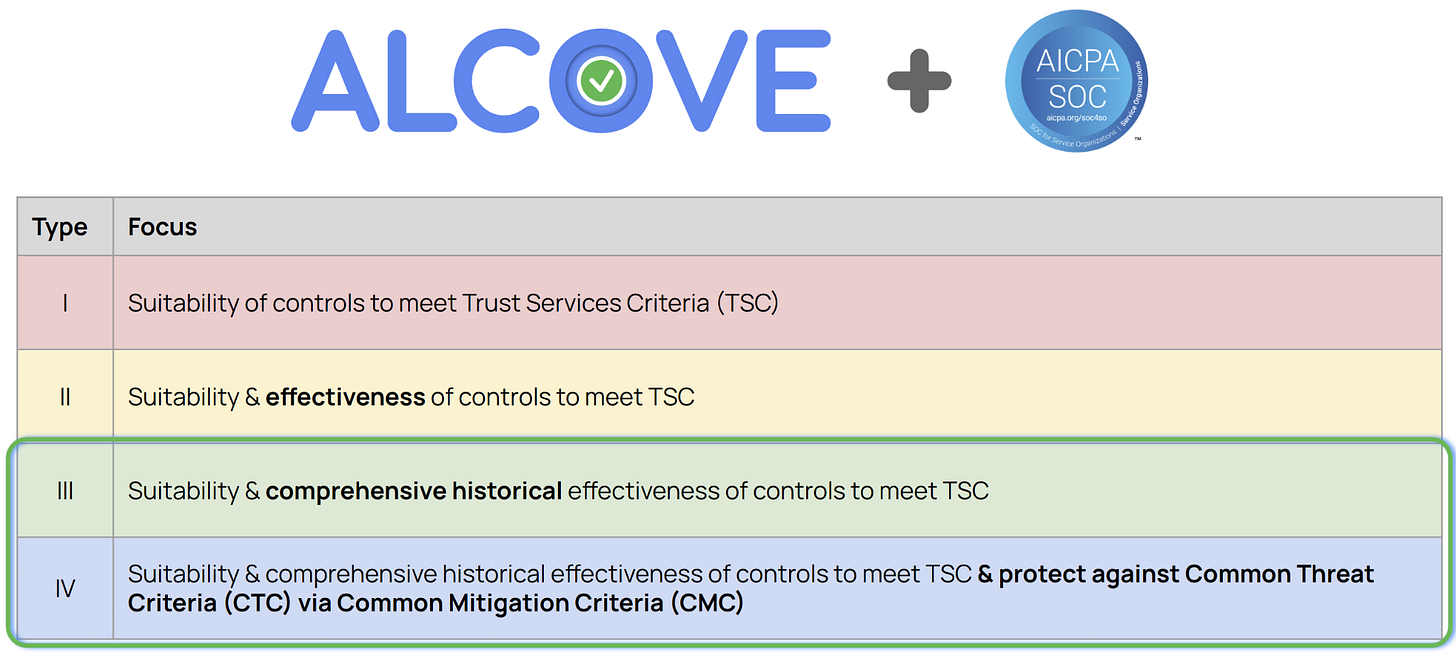

Here’s what it could look like to integrate ALCOVE with SOC 2:

SOC 2 Type I and Type II reports would still exist in this world and still provide (limited) value for organizations and their stakeholders. However, we can extend SOC 2 report types to Type III and Type IV so SOC 2 can provide higher levels of assurance in line with ALCOVE Level 3 and Level 4.

In order for this to truly overcome the three fundamental flaws I outlined above, we need to also evolve our control requirements and reporting artifacts.

In the world of ALCOVE, SOC 2’s TSCs would be more rigorous, incorporating Common Threat Criteria and Common Mitigation Criteria to ensure organizations are implementing relevant controls that are well known to protect against relevant threats so that sufficient assurance can be clearly and unambiguously provided about control operating effectiveness. Here’s an example of what that could look like - the text in black below is existing text from SOC 2’s TSC language, and the text in red are the additional ALCOVE-related control requirements:

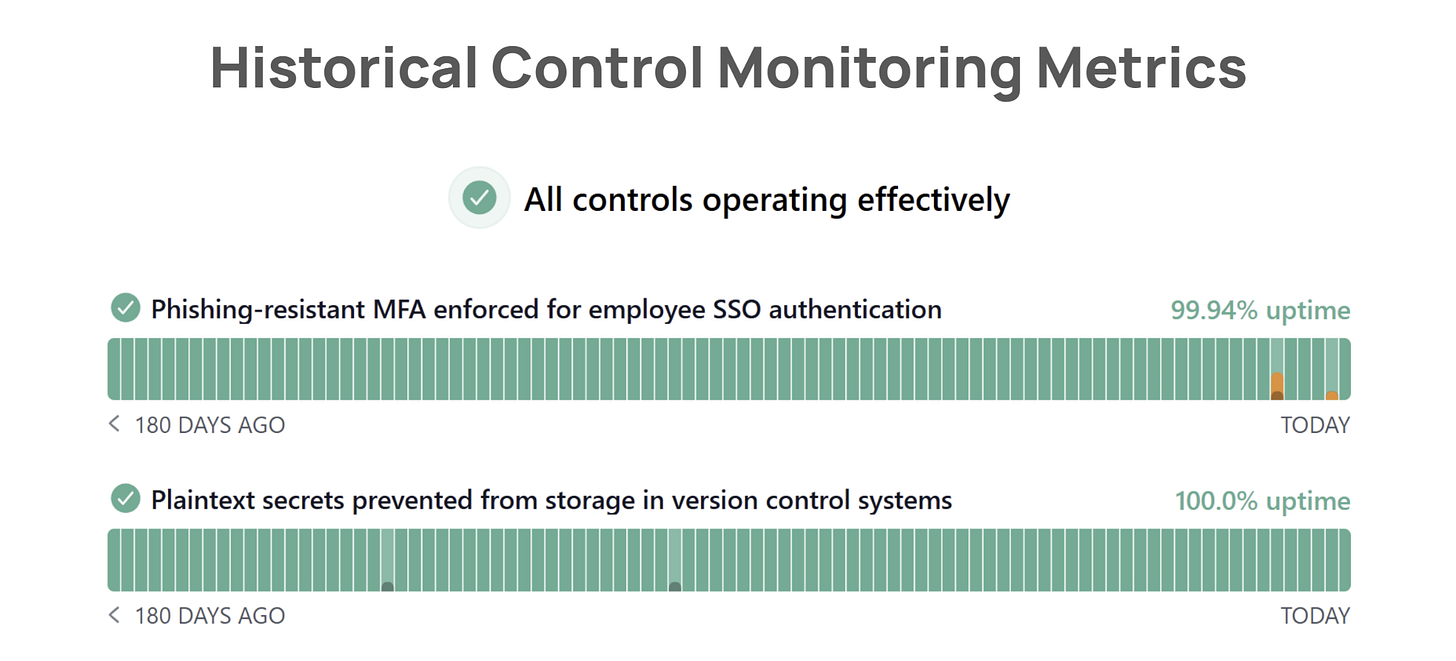

Finally, we need to revamp our security compliance reporting artifacts so they’re as dynamic as the control environments we’re trying to provide in-depth continuous assurance around. In addition to providing an audit report, with rich context about an organization’s system, architecture, controls, and an auditor’s opinion about control operating effectiveness, we also need control operating effectiveness metrics that capture current and historical operating effectiveness. Much in the same way that StatusPage created a new paradigm for providing transparency around an organization’s system uptime and availability, an ALCOVE-specific reporting artifact would look something like this:

While existing Trust Center products on the market today provide Key Control Indicator (KCI) metrics about an organization’s controls, they are, quite frankly, junk. They only tell you what the “current state” of an organization’s controls are like. And in some cases, certain Trust Center products will hide/remove a control (and its corresponding green checkmark) when the control is in a failing state. This is pure unadulterated security assurance theater. In order for real-time control operating effectiveness dashboards to truly provide in-depth continuous assurance, they must provide an honest representation of an organization’s controls, both current and historical states.

As excited as I am about how a framework like ALCOVE could help provide stronger assurance about control operating effectiveness, there is a big obstacle to adopting a more rigorous approach like it: incentives.

Overcoming the obstacle of misaligned incentives

Right now, incentives around security compliance audits are skewed in the wrong direction: many organizations, especially smaller and newer companies, are incentivized to pursue cheaper and weaker audits that don’t sufficiently scrutinize their controls. This distorts market signals about organizations’ risk profiles, especially when third-party due diligence teams rely on basic compliance requirements to “allow” vendors into their environment (“Do you have a SOC 2 Type II without a qualified opinion or any exceptions? Ok, great, now answer these 500 other questions about your security practices - be honest! If your answers look good enough, you’ll win our $200k ARR contract.” Let’s not kid ourselves: these incentives are so horribly misaligned.)

Additionally, third party security risk management teams aren’t usually empowered to make risk-taking decisions for other stakeholders at their organization, who are looking to use a vendor solution due to the outsized value they stand to gain from doing so. Third party security risk assessments are typically highly inefficient and take too much time to get to a decision about whether or not to proceed with a vendor given their risk profile. Teams that take weeks to assess a vendor that they would then want to say “no” to because of weak security controls will get bulldozed over by leaders at their organization. In so doing, they will burn through political capital, undermining trust in their team and function across their organization which can create feelings of job insecurity. In other words: third party security risk management teams have neither the leverage nor incentive to say “no” to a vendor that provides weak assurance about their security controls.

One way we could course correct incentives in this dynamic? By better integrating cyber insurance into the mix!

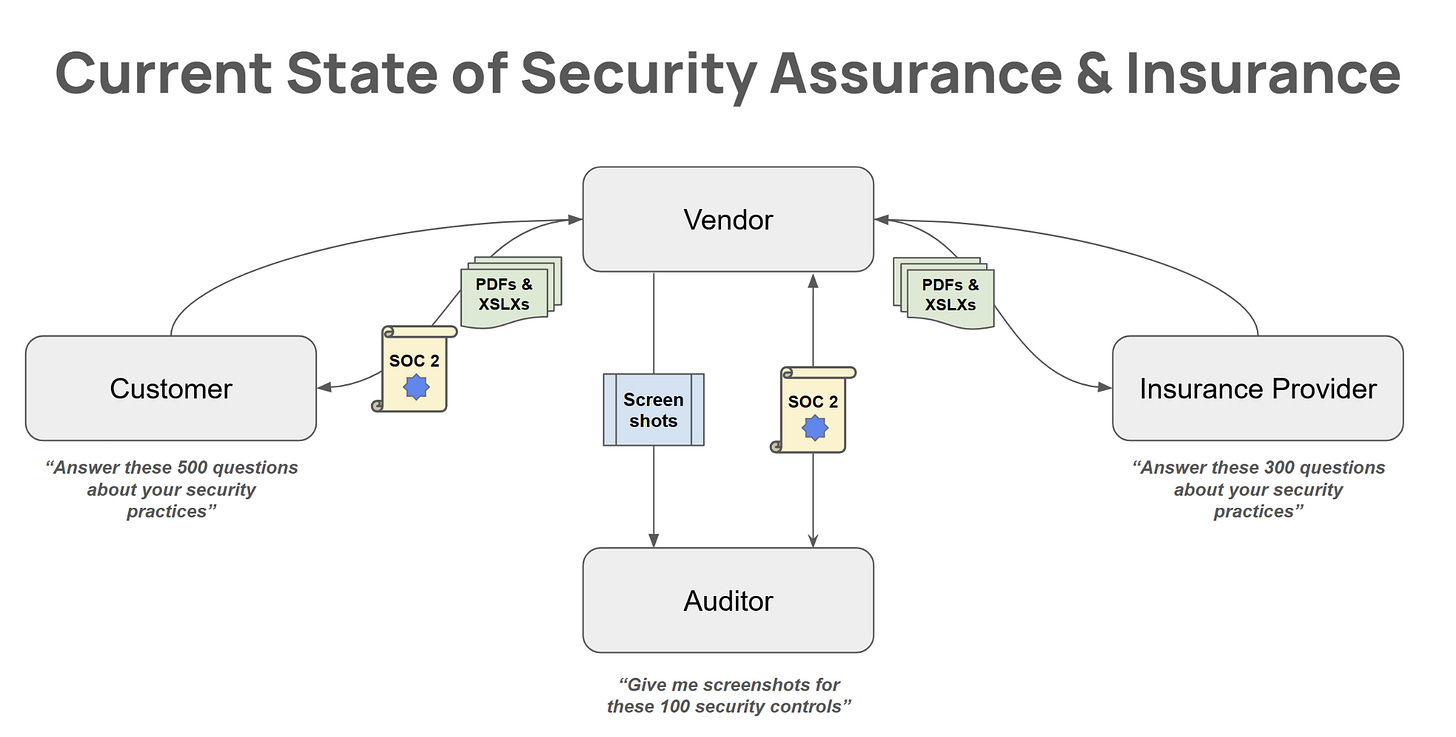

Here’s what the current state of our “security assurance & insurance” dynamic looks like in the world:

The incentives that exist in this dynamic are as follows:

Auditors want to grow their customer base and make more money, meaning they want to avoid upsetting their customers with lengthy cumbersome audits that could result in them getting a “failing grade.”

Customers are of two minds: the actual customer team for a vendor’s solution wants to get their hands on said solution ASAP. Third-party risk management teams are encumbered by contradictory fears: the fear of approving an overly-risky vendor (which if said vendor experiences a security incident, third-party risk management teams fear they will be held accountable for making a bad risk decision); and the fear of saying “no” resulting in backlash from the customer team.

Vendors want fast, easy, and cheap audits so they can win more business and keep their sales cycle running efficiently.

Insurance providers want to grow their customer base and make more money while reducing uncertainty about the risk pool they’re managing, such that they reduce the likelihood and size of claim payouts.

At the end of the day, all players are motivated by two fundamental incentives: spend less resources to get more value.

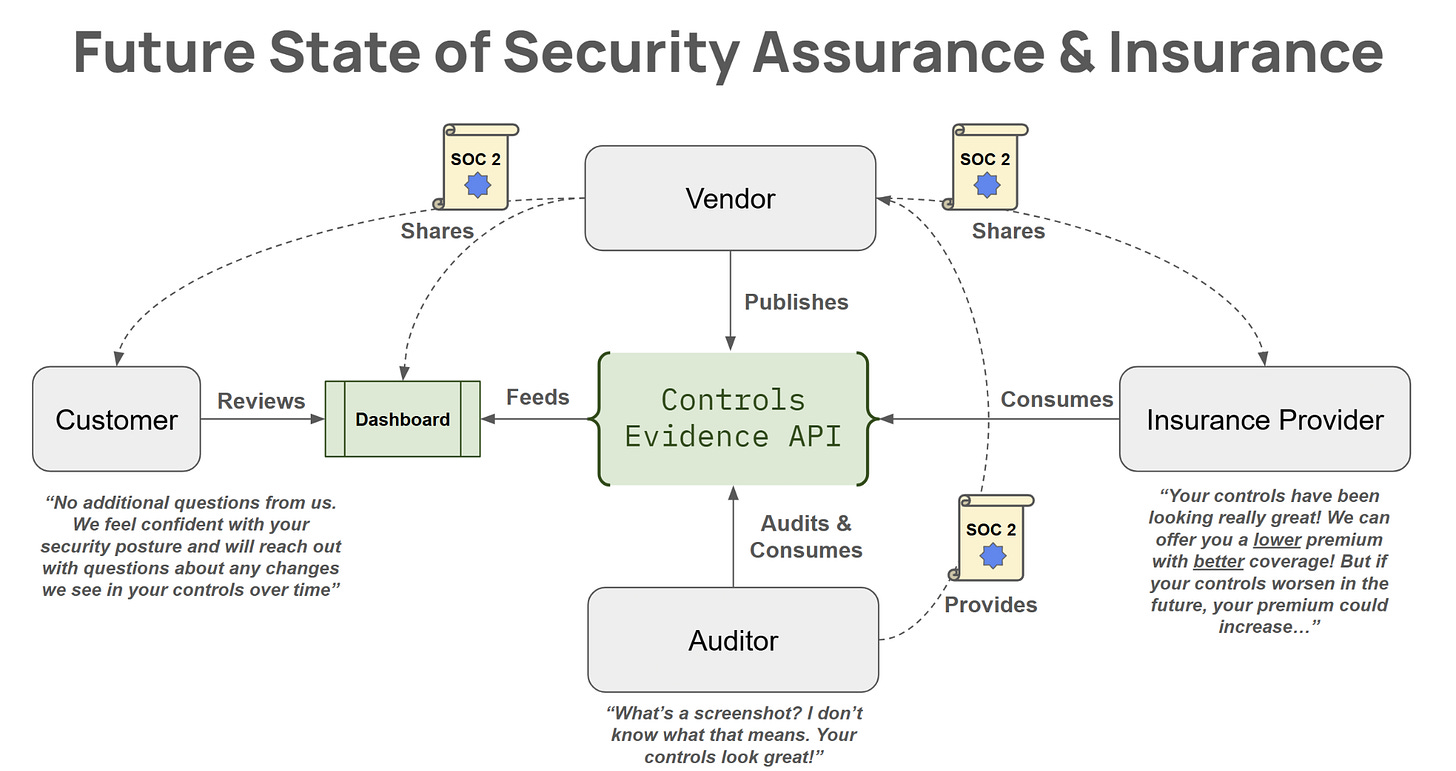

So what would a better model look like where incentives are better aligned in a way that actually could drive improved controls across organizations through stronger assurance signals being provided by vendors to other stakeholders?

I am going to draw inspiration for this idea from two sources: the Artificial Intelligence Underwriting Company, which is pioneering a novel AI Assurance + Insurance framework called AIUC-1 (which, you may notice, is very ALCOVE-esque); and Progressive Insurance’s Snapshot offering, which allows drivers to get discounts on their car insurance while allowing Progressive to reduce uncertainty about their risk pool via automated continuous monitoring of driving behavior.

Now the incentives change, driven largely by insurance providers who have the most leverage of any other stakeholder in this picture. All organizations currently have a strong incentive to transfer cyber risk to insurance providers in order to avoid experiencing catastrophic losses (for example, through extensive outages and system disruptions caused by ransomware).

Insurance providers have a great opportunity to push vendors to automatically and continuously feed them evidence about their controls, instead of gathering context via questionnaires once per year.

Vendors stand to save money on their cyber insurance premiums with the same, or potentially better, coverage, which of course requires them to ensure their controls are continuously operating effectively!

Auditors stand to have an easier time performing faster, more efficient and more rigorous audits.

Customers stand to gain stronger assurance, at the time they perform due diligence and continuously thereafter.

Did I just solve all of the world’s cybersecurity problems???

(I kid, I kid)

In conclusion

All of this is very much wishful thinking on my end. But we as a civilization have achieved crazier things in less opportune circumstances (see: sending humans to the Moon and back in a fancy metal pressurized can using 1960s-era technology).

What do you think of this? What seems like it would work or not work about these ideas? What would make it more viable?

The historical analysis, I think is incredibly helpful for orgs to show they're taking security seriously; from postmortem findings of deficiencies, to improvements, to monitoring and measuring. As well as an incremental roll-out and increased coverage.

In addition to the point about 'we rarely do two releases and builds a year' (rephrasing, because that's how things used to work), any new standard I think needs to be almost as binary as PCI-DSS: yes/no/compensating controls/out-of-scope.

It's very easy, say, to not chose 'privacy' as a Trust Services Criteria/Principle — I'm not sure many people would notice it's not in the (stale) report. Or indeed, you might exclude certain parts of the estate. I'd really like it if a new standard clearly states org structure and estate, along with what's excluded and the justification/risk assessment of why that's the case.

Audit reports are traditionally, point-in-time, and in a fast-moving organization may already be out of date by the time they're assessed — especially if the auditors/assessors aren't looking at things end-to-end — it's very easy to narrate a story, but if that's no longer the case, or is about to be replaced/changed, then yikes.

I'd get value from a benchmark of organziational agility / velocity of transformation/change to add some weighting to my review.